Validation of TLMBHT to solve the Pennes equation in time-domain for one-dimension using line elements

Jan 31, 2017 by Hugo Milan

Here, I will walk you through in how to validate the TLM method to solve the Heat equation in 1D with the element Line by comparing the tlmbht predictions with analytical solution predictions.

Everything you need is available in the folder /vte/generalDiffusion/1D/LineNode. This folder was downloaded when you downloaded the source files. If you did not download the source files, you can download it from here. If you do not want to, you do not need to download or install anything–all the relevant outputs will be shown here. If you want to download tlmbht, go to releases and get the most updated version of tlmbht.

In this validation, we will follow the 5 steps showed here.

1) Create the geometry of the problem.

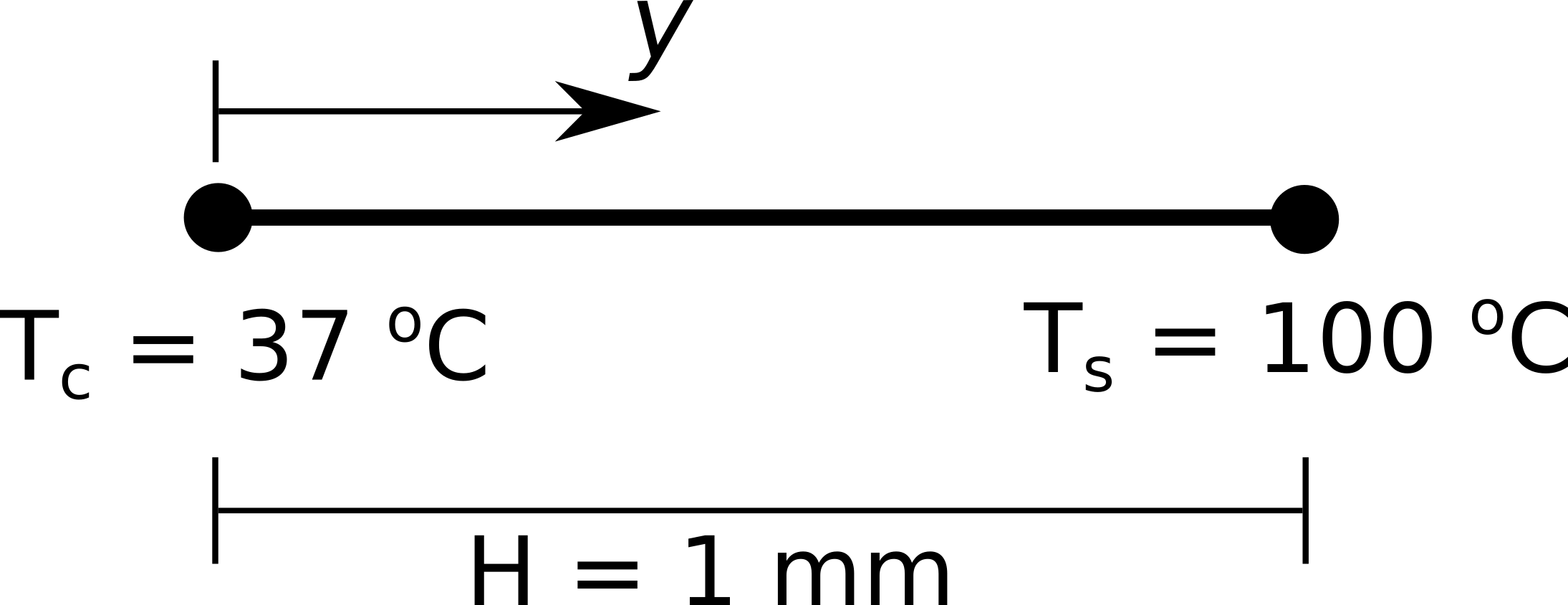

We will consider a simple one-dimensional problem that has analytical solution. In this problem, we will include the effect of blood perfusion, metabolic heat generation, and two constant temperatures boundary conditions (constant core temperature TC, and constant surface temperature TS). This may represent the increase in temperature when the human skin gets in contact with a hot surface. The problem geometry is shown below.

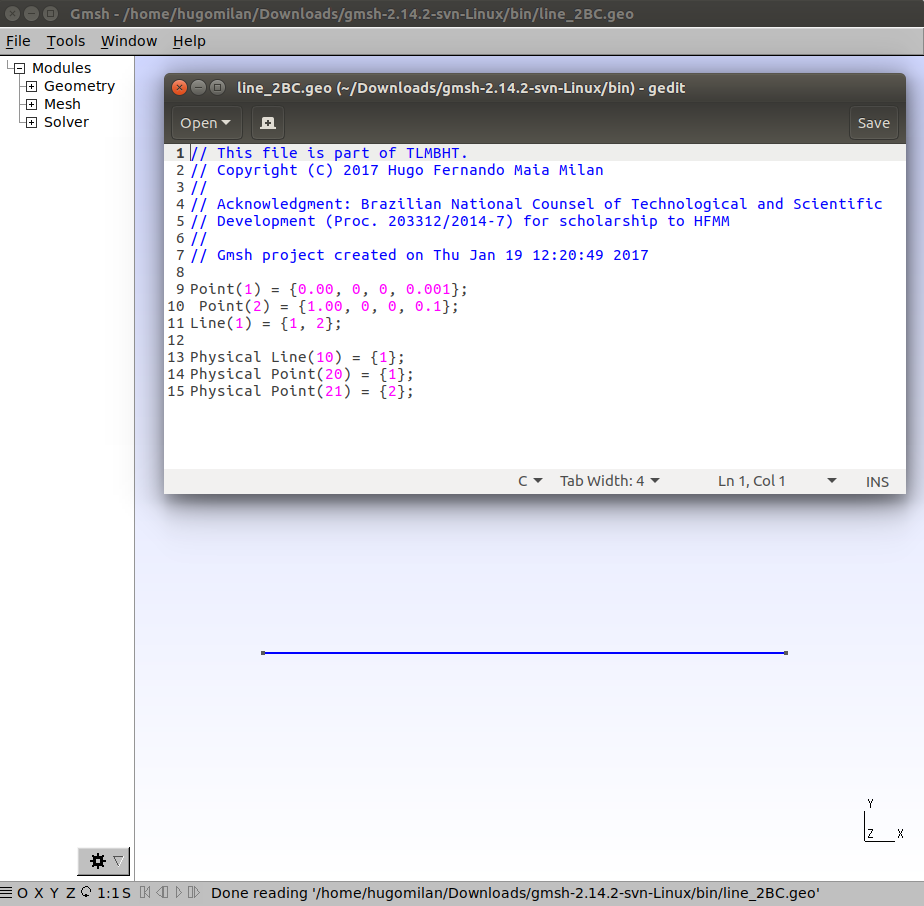

Now that we defined the problem, we need to draw the problem geometry using a format that tlmbht knows how to read. This was already done for you. The geometry of the problem was created using gmsh. The script file is line_2BC.geo. Note in the script file that we chose different sizes for the points (the last value in the Points’ line). This will make a mesh of line elements that differ in size. You can also see in the script file that we put ‘Physical tags’ in the Line geometry and in the Points. We did this so that we can tell tlmbht which tag is for material (number 10) and which tag is for boundary (number 20 and 21).

Now we are ready to create the mesh.

2) Create the mesh of the problem.

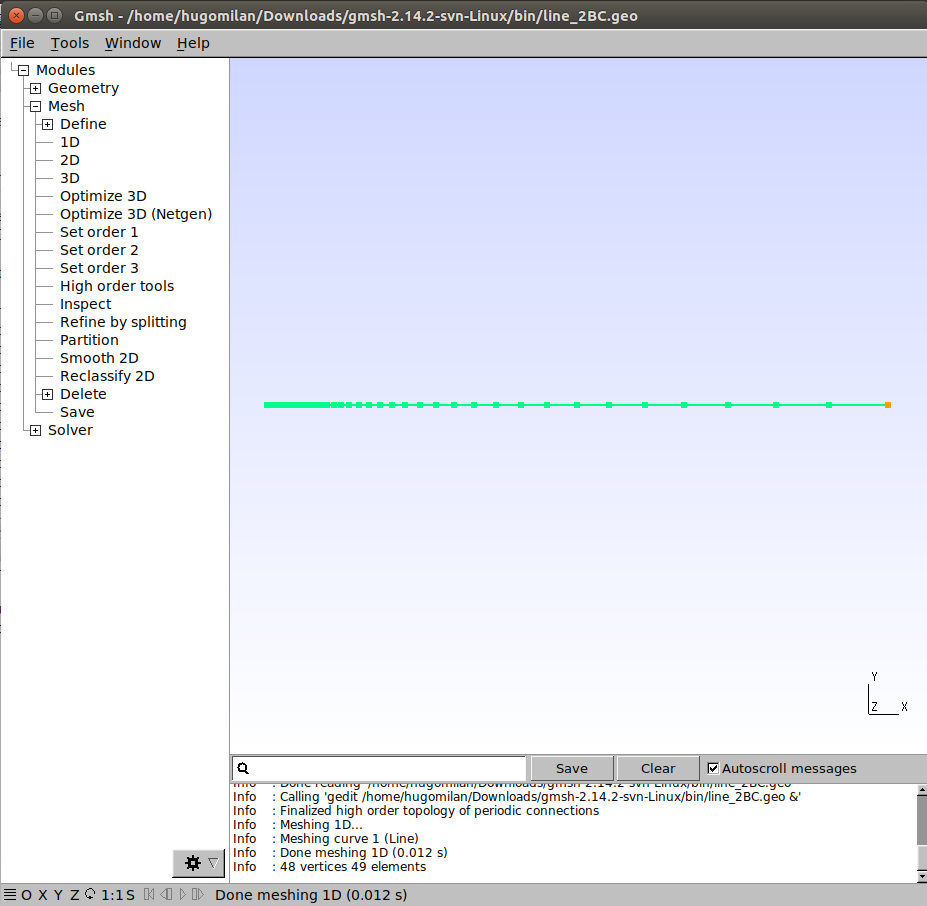

The mesh was easily created using gmsh/Mesh/1D. The mesh file (already converted to tlmbht native mesh format) is line_2BC.tbn It contains 48 points (vertices) and 47 line segments (elements). You can also see that the line segments are shorter (the mesh is denser) near the point that we set a smaller size for the point.

Now we are ready to create the description of the problem

3) Create the description of the problem.

The description of the problem is in the file cpennes1Li.tlm. Here, I will explain how this case file was configured. However, if you are in a hurry, you can go skip this part and move on to the next section.

Explanation of this case file

The case file is structured in headers and I will go over every header in the file cpennes1Li.tlm. The first header you see (Simulation), is used to configure parameters common to the equations of the problem. In this case, we are only configuring the output extension to the ‘m’ (Octave/Matlab m format) so that it is easier to run the validation algorithm.

Simulation

{

output extension = m;

}

The Mesh header contains information about the mesh. Here we tell the software which mesh to use (“file name”) and in what format it is (“input format”).

Mesh

{

file name = line_2BC_47e;

input format = tlmtbn;

}

The Equation header tells the software what equation it should solve and how. You can have different Equations headers to defined different equations being solved simultaneously in a multi-physical problem. In the Equation header, we define the type of equation and give it a name. The name is essential to link what is in the Equation header with what is in the Material and Boundary headers. Then, we define the dimension of the problem and tell tlmbht to solve this problem in the time-domain (“Solve = dynamic”). Since we are solving a time-domain problem, we need to define the time-step and the final simulation time. The “time-jump” is a configuration that tells tlmbht after how many time-steps it should save the output data (which is defined in the “save” options). Here, we are saving at every 100 time-steps, which is equivalent to saving at every 100 ms. Note that these 100 time-steps are all solved.

Equation

{

type = diffusion;

equation name = heat_name;

dimensions = 1;

Solve = dynamic;

time-step = 1e-3;

time-jump = 100;

final time = 1;

save = scalar;

save = scalar between;

save = vector;

}

The Material header defines the properties of the equation. You can have different Material headers for different properties in the same problem. We tell tlmbht to what equation this Material header is referred to by giving it the equation name (“BHE”). In number, we give the Material header the Physical tag number that we gave to the elements during the mesh generation. Therefore, the options we input here are going to be applied to the elements with tag number 10. Finally, we defined density, specific heat, thermal conductivity, blood perfusion, blood density, blood specific heat, blood temperature, internal heat generation, and initial temperature (required for time-domain simulations).

Material

{

equation = BHE;

number = 10;

density = 1200;

specific heat = 3200;

thermal conductivity = 0.3;

blood perfusion = 1e-4;

blood density = 1052;

blood specific heat = 3600;

blood temperature = 37;

internal heat generation = 500;

initial temperature = 37;

}

The Boundary header defines the boundary conditions. You can have different Boundary headers for different boundary conditions and for each equation being solved. We proceed similar to what we did in the Material header. That is, we define the equation name and the Physical tag number that this boundary will be applied to. Since our boundary conditions are for defined temperatures, we defined the “temperature” options that tells tlmbht that these boundaries are for fixed temperature values.

Boundary

{

equation = BHE;

number = 20;

Temperature = 37;

}

Boundary

{

equation = BHE;

number = 21;

Temperature = 100;

}

The file cpennes1Li_full.tlm contains additional explanation about the input. If you want more information in how to configure the case file, go to How to configure a case file.

4) Solve the problem.

Click here if you have Windows and need help to run tlmbht in your machine.

If you have the tlmbht binary in your path environment, simply type tlmbht cpennes1Li.tlm. If you don’t have it in your path environment, you may copy the binary to the folder /vte/generalDiffusion/1D/LineNode/ and then type ./tlmbht cpennes1Li.tlm. In some seconds, the calculation will be done.

If you want to see what is going on internally, you may run tlmbht with –verbose. If you want to see how long does it take to run tlmbht, you may run it with –timing. The command to run with both is simply tlmbht cpennes1Li.tlm --verbose --timing.

Now we are ready to visualize the output and compare the TLM predictions with an analytical prediction.

5) Visualize the output.

After you have run tlmbht, it created the output file cpennes1Li.m. In this tutorial, you do not need to worry about this file. We will run a script that automatically loads the data into Octave/Matlab. The script is the file vpennes1Li.m, which calls the analytical solver function D1_BHE_f.m (click here to read more about the analytical solution and how to use this function).

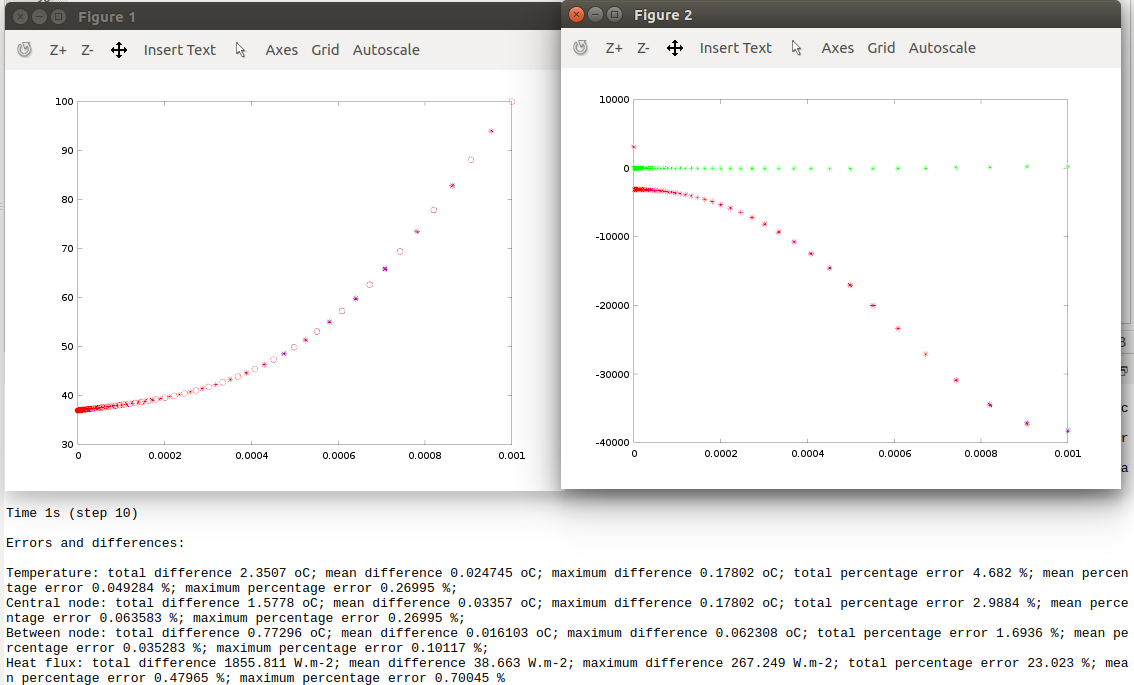

This part should be as simple as opening vpennes1Li.m in Octave/Matlab and running it (press key F5). It will show you two plots and textual information. The figure below shows the two plots and part of the textual information. Temperature is shown in the left figure and heat flux is shown on the right figure. The analytical predictions are shown in blue, the tlmbht predictions are shown in red, and the green shows the difference of the calculated heat fluxes. In the temperature plots, asterisks represent temperatures calculated at the center of the TLM nodes and the circles represent the temperatures calculated between nodes. You can see that the predictions are almost identical, which you can confirm by looking at the textual information that tells you that the mean temperature error was 0.05 % and the mean heat flux error was 0.48 %.

You may note in the heat flux plot that there is a left most point with positive values while all the other points have negative values. This is because this is the point at the boundary and it represents heat flux going from the medium to that boundary. The negative values are representing the heat fluxes going into the direction of the higher temperature value, which means that the medium is acquiring, and not loosing, heat, as we would expect from our problem.

You are not satisfied with this accuracy? Well… this is a numerical method; we will never get the same exact numbers as the analytical solution gives. Besides, this analytical solution is based on a infinity sum and, by default, the script vpennes1Li.m only considers the first 50 terms. If you insist, you can try to increase the number of terms in the analytical solution. Then, as it is true for numerical methods, you can try to increase the number of elements and/or decrease the time-step. These changes will increase the computational time but also increase the accuracy.

Done!

I hope you have enjoyed this validation section! You may now try to change the case file (cpennes1Li.tlm) and see what happens. Remember that if you change any parameter in the cpennes1Li.tlm file you will need to do the same in the vpennes1Li.m file. Except for time and space positions, they are not linked.

Remember: you are using a powerful numerical solver. You do not need to be constrained by solutions that can be solved analytically. Explore! Try different boundary conditions, include more materials, etc. Make this problem more realistic!

Now, you can go to: