Analytical solution of the Diffusion/Heat equation in time-domain for two-dimensions

Jan 30, 2017 by Hugo Milan

You can download the algorithm D2_HEAT_f.m for Octave/Matlab that can solve this problem here and you can see instructions in how to use it here. If you want to see the final solution, go to Solution.

In this page, we will solve the dynamic diffusion/heat equation in two-dimensions using the principles of superposition and separation of variables. We build on the previous solution of the diffusion/heat equation in one-dimension described here to solve this two-dimensional problem. The problem we will solve is restricted to the following initial and boundary conditions:

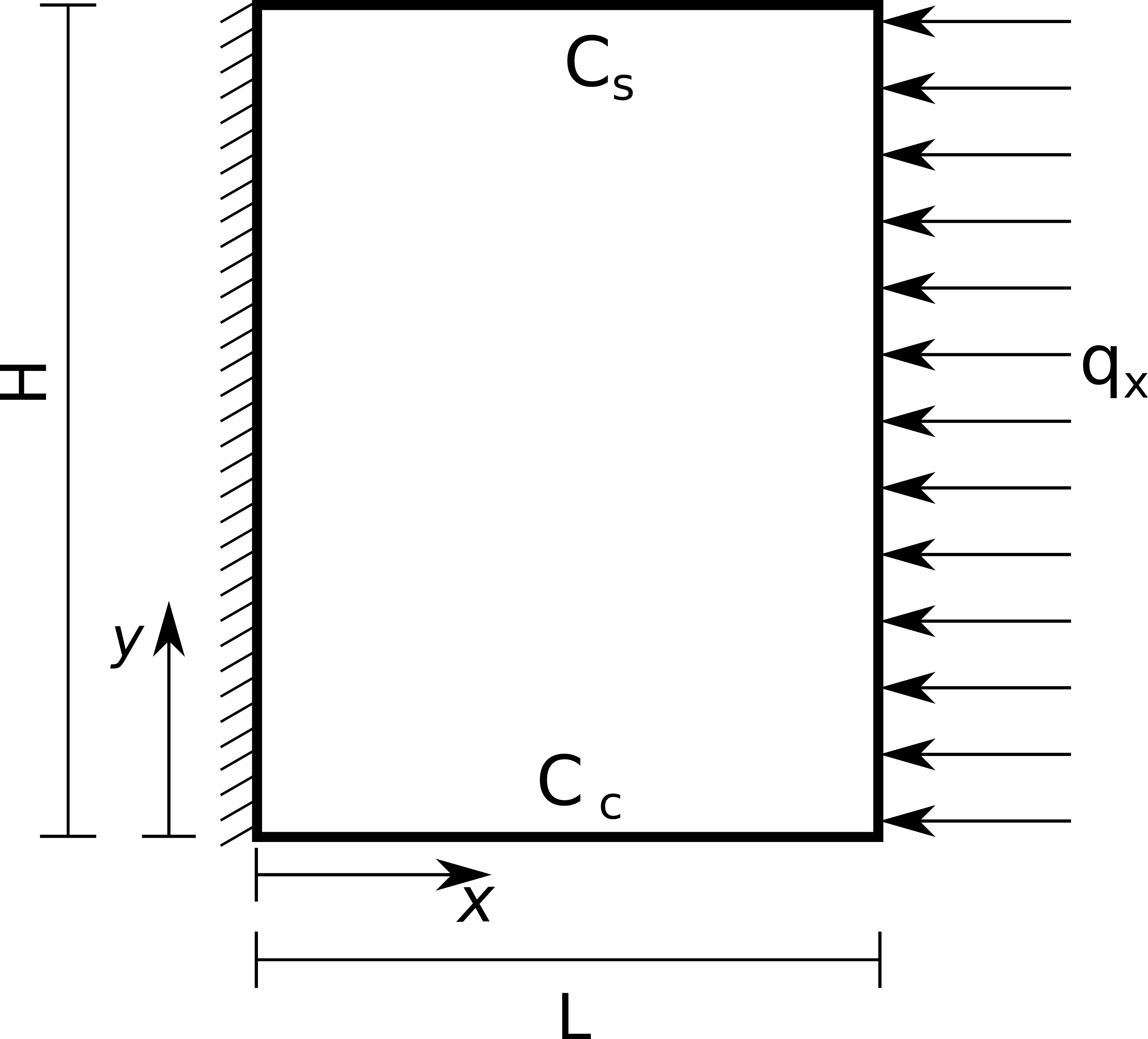

The problem geometry for the diffusion equation can be represented as shown below.

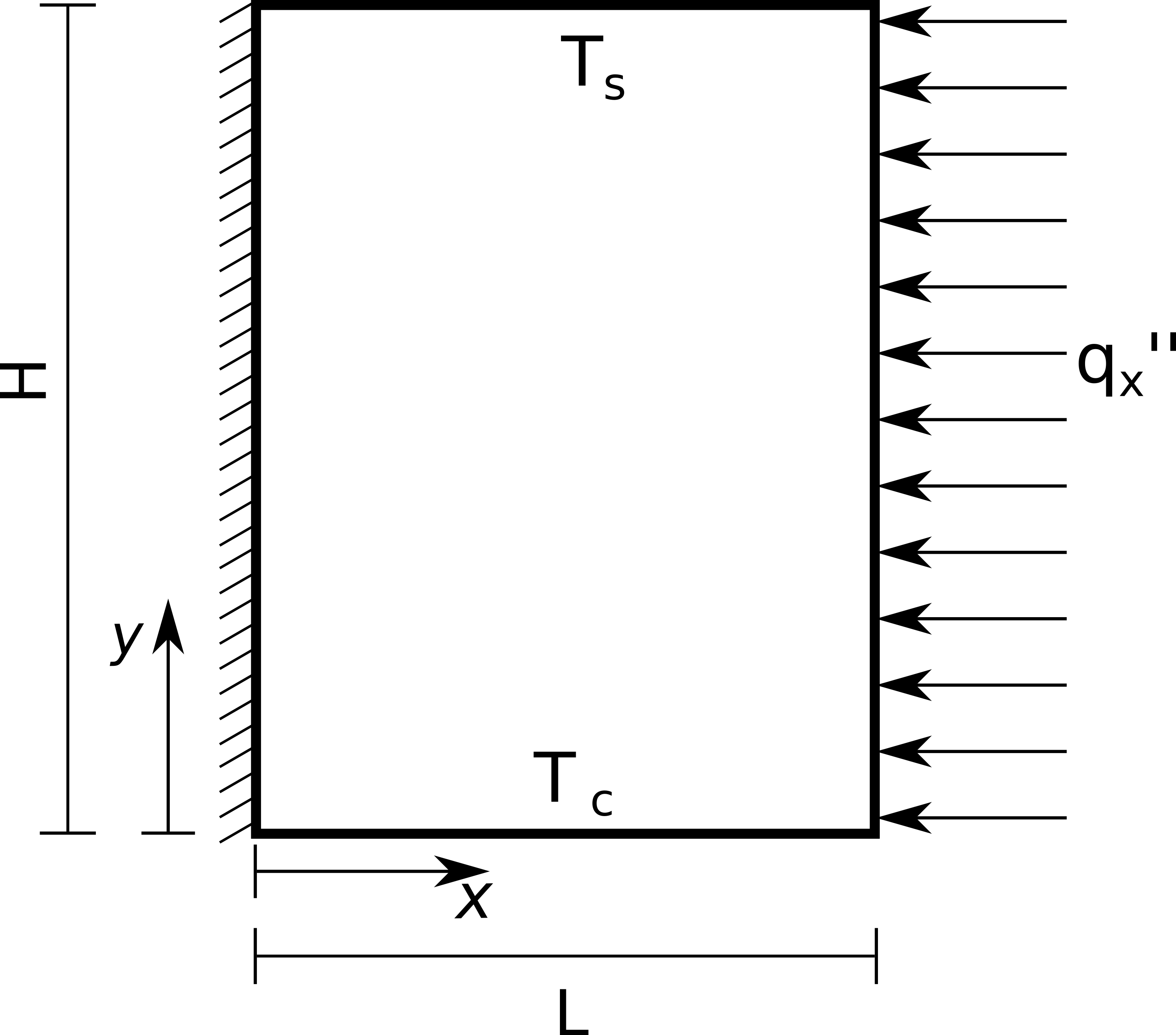

The problem geometry for the heat equation can be represented as shown below.

This geometry is a plate in a three-dimensional space, as you can see in the three-dimensional model below.

Governing equations

Diffusion equation:

\begin{equation} \frac{\partial C}{\partial t} = D\left(\frac{\partial^2 C}{\partial x^2} + \frac{\partial^2 C}{\partial y^2} \right) + S \end{equation}

where \(C\) is concentration, \(t\) is time, \(D\) is diffusivity, and \(S\) is source.

And we define the heat equation as:

\begin{equation} \rho c_{p}\frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = k\left( \frac{\partial^2 T}{\partial x^2} + \frac{\partial^2 T}{\partial y^2} \right) + S \label{eq:Heat} \end{equation}

where \(T\) is temperature, \(t\) is time, \(\rho\) is density, \(c_{p}\) is specific heat, \(k\) is heat conductivity, and \(S\) is source.

Note that the diffusion equation and the heat equation have the same form when \(\rho c_{p} = 1\).

Solving

I will show the solution process for the heat equation. The solution process for the diffusion equation follows straightforwardly.

I will use the principle of suporposition so that:

\begin{equation} T(x, y,t) = T_c + \phi_a(y) + \phi_b(y)\tau_b(t) + \phi_c(x, y) + \phi_d(x,y)\tau_d(t) \label{eq:Sup} \end{equation}

and the initial and boundary conditions for these problems are:

Applying Eq. \ref{eq:Sup} in \ref{eq:Heat} yields

\begin{equation} \left( k\frac{\partial^2 \phi_a}{\partial y^2} + S \right) - \left( \rho c_{p}\phi_b\frac{\partial \tau_b}{\partial t} - k\tau_b\frac{\partial^2 \phi_b}{\partial y^2} \right) = \ldots\\ \ldots \left( -k \frac{\partial^2 \phi_c}{\partial x^2} - k \frac{\partial^2 \phi_c}{\partial y^2} \right) + \left( \rho c_{p}\phi_d\frac{\partial \tau_d}{\partial t} - k \tau_d\frac{\partial^2 \phi_d}{\partial x^2} - k \tau_d\frac{\partial^2 \phi_d}{\partial y^2} \right) \end{equation}

which implies that we can solve Eqs. \ref{eq:a}-\ref{eq:d} \begin{equation} k\frac{\partial^2 \phi_a}{\partial y^2} + S = 0 \label{eq:a} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \rho c_{p}\phi_b\frac{\partial \tau_b}{\partial t} - k\tau_b\frac{\partial^2 \phi_b}{\partial y^2} = 0 \label{eq:b} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} k \frac{\partial^2 \phi_c}{\partial x^2} + k \frac{\partial^2 \phi_c}{\partial y^2} = 0 \label{eq:c} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \rho c_{p}\phi_d\frac{\partial \tau_d}{\partial t} - k \tau_d\frac{\partial^2 \phi_d}{\partial x^2} - k \tau_d\frac{\partial^2 \phi_d}{\partial y^2} = 0 \label{eq:d} \end{equation}

Solving Eq. \ref{eq:a} and \ref{eq:b}

The solution of Eq. \ref{eq:a} and \ref{eq:b} was previously covered when we solved the diffusion/heat equation in one-dimension.

Solving Eq. \ref{eq:c}

We will use separation of variables to solve Eq. \ref{eq:c}. In separation of variables, we assume that the solution is the multiplication of a function of \(x\) ( \(\phi_{cx}(x)\) ) and \(y\) ( \(\phi_{cy}(y)\) ). Hence,

\begin{equation} \frac{1}{\phi_{cx}}\frac{\partial^2 \phi_{cx}}{\partial x^2} = -\frac{1}{\phi_{cy}}\frac{\partial^2 \phi_{cy}}{\partial y^2} = \gamma_n^2 \end{equation}

The solution of \(\phi_{cy}\) can be expressed as:

\begin{equation} \phi_{cy} = c_6 \sin{\left(\gamma_n y\right)} + c_7 \cos{\left(\gamma_n y\right)} \end{equation}

Applying the boundary condition at \(y = 0\) we get \(c_7 = 0\). Applying the boundary condition at \(y = H\) we get:

\begin{equation} \sin{\left(\gamma_n H\right)} = 0 \label{eq:gamman} \end{equation}

which implies that

\begin{equation} \gamma_n = \frac{n\pi}{H} \end{equation}

with \(n = 1, 2, 3, \dotsc\) We start the counting from \(1\) because \(n = 0\) yields \(\phi_{cy} = 0\). The solution of \(\phi_{cx}\) can be expressed as:

\begin{equation} \phi_{cx} = c_8 \sinh{\left(\gamma_n x\right)} + c_9 \cosh{\left(\gamma_n x\right)} \end{equation}

Applying the boundary condition at \(x = 0\) we get \(c_8 = 0\). Then, the solution that we are looking for is:

\begin{equation} \phi_c = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} c_n \cosh{\left(\gamma_n x\right)}\sin{\left(\gamma_n y\right)} \label{eq:c:almost} \end{equation}

Now, we apply the non-homogeneous boundary condition at \(x = L\):

\begin{equation} \frac{\partial\phi_c}{\partial x}(x = L) = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} c_n \gamma_n\sinh{\left(\gamma_n L\right)}\sin{\left(\gamma_n y\right)} = \dfrac{q_x}{k} \label{eq:c:cn} \end{equation}

To solve Eq. \ref{eq:c:cn}, we multiply both sides by an orthogonal function of the function that multiplies \(c_n\) and integrate it from \(y = 0\) to \(y = H\) to elimate the \(y\) dependence. That is, we need a function that is orthogonal to \(\sin{\left(\gamma_n y\right)}\). The function that we are looking for is \(\sin{\left(\gamma_m y\right)}\). Multiplying both sides by this function yields

\begin{equation} \int_{y=0}^{y=H}\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}c_n \gamma_n\sinh{\left(\gamma_n L\right)}\sin{\left(\gamma_n y\right)}\sin{\left(\gamma_m y\right)} dy = \int_{y=0}^{y=H}\dfrac{q_x}{k}\sin{\left(\gamma_m y\right)} dy \label{eq:b:cn2} \end{equation}

Since we have

\begin{equation} \int_{y=0}^{y=H} \sin{\left(\gamma_n y\right)}\sin{\left(\gamma_m y\right)} dy = 0 \label{eq:mnn} \end{equation}

for \(n \neq m\), and

\begin{equation} \int_{y=0}^{y=H} \sin{\left(\gamma_n y\right)}\sin{\left(\gamma_m y\right)} dy = \frac{H}{2} \label{eq:mn} \end{equation}

for \(n = m\), we can drop the summation and solve Eq. \ref{eq:b:cn2} for each \(c_n\):

\begin{equation} c_n = \dfrac{\displaystyle \dfrac{q_x}{k}\int_{y=0}^{y=H}\sin{\left(\lambda_n y\right)} dy}{ \displaystyle \gamma_n\sinh{\left(\gamma_n L\right)}\int_{y=0}^{y=H}\sin^2{\left(\lambda_m y\right)} dy } \label{eq:b:cn3} \end{equation}

The solutions of the integral on the numerator is:

\begin{equation} \int_{y=0}^{y=H} \sin{\left(\gamma_n y\right)} dy = \frac{1}{\gamma_n}\left[1 - \cos{ \left( \gamma_n H\right) } \right] \end{equation}

From the definition of \(\gamma_n\) in Eq. \ref{eq:gamman},

\begin{equation} \int_{y=0}^{y=H} \sin{\left(\gamma_n y\right)} dy = \frac{1}{\gamma_n}\left[1 - \left( -1 \right)^n \right] \label{eq:c:int} \end{equation}

From Eq. \ref{eq:c:int} it is obvious that the summation in Eq. \ref{eq:c:almost} will be non-zero only for odd values of \(n\). Hence, we define

\begin{eqnarray} n &=& 2o - 1\\ \gamma_o &=& \frac{ \left( 2o - 1 \right) \pi}{H} \end{eqnarray}

Therefore, the final solution of Eq. \ref{eq:c} is:

\begin{equation} \phi_c = \sum_{o=1}^{\infty} \frac{4q_x}{Hk\gamma_o^2 \sinh{\left(\gamma_o L\right)} } \cosh{\left(\gamma_o x\right)}\sin{\left(\gamma_o y\right)} \label{eq:c:final} \end{equation}

Solving Eq. \ref{eq:d}

We will use separation of variables to solve Eq. \ref{eq:d}. In separation of variables, we assume that the solution is the multiplication of a function of \(x\) ( \(\phi_{dx}(x)\) ) and \(y\) ( \(\phi_{dy}(y)\) ) and \(t\) \( ( \tau_d(t) ) \). Hence,

\begin{equation} \frac{\rho c_p}{k \tau_d}\frac{\partial \tau_d}{\partial t} = \frac{1}{\phi_{dx}}\frac{\partial^2 \phi_{dx}}{\partial x^2} + \frac{1}{\phi_{dy}}\frac{\partial^2 \phi_{dy}}{\partial y^2} = - \eta_p^2 \end{equation}

Defining \(\alpha = k/( \rho c_p ) \), the solution of \( \tau_d \) is expressed as:

\begin{equation} \tau_d = c_{10}\exp{\left( -\alpha\eta_p^2 t \right)} \end{equation}

Now, to solve for \( \phi_d \), we define:

\begin{equation} \frac{1}{\phi_{dx}}\frac{\partial^2 \phi_{dx}}{\partial x^2} = - \frac{1}{\phi_{dy}}\frac{\partial^2 \phi_{dy}}{\partial y^2} - \eta_p^2 = - \beta_r^2 \end{equation}

Hence, the solution of \( \phi_{dx} \) is:

\begin{equation} \phi_{dx} = c_{11}\sin{ \left( \beta_r x \right) } + c_{12}\cos{ \left( \beta_r x \right) } \end{equation}

Applying the boundary condition at \(x=0\) yields \(c_{11}=0\). Applying the boundary condition at \(x=L\):

\begin{equation} \frac{\partial\phi_{dx}}{\partial x}(x=L) = 0 = \sin{ \left( \beta_r L \right) } \end{equation}

which implies that

\begin{equation} \beta_r = \frac{r\pi}{L} \label{eq:d:beta} \end{equation}

with \(r=0,1,2,\ldots\) We start counting in 0 because \(r=0\) does not necessarily imply \(\phi_{dx}=0\). Now, the solution of \(\phi_{dy}\) is:

\begin{equation} \phi_{dy} = c_{13}\sin{ \left( y\sqrt{\eta_p^2 - \beta_r^2} \right) } + c_{14}\cos{ \left( y\sqrt{\eta_p^2 - \beta_r^2} \right) } \end{equation}

Applying the boundary condition at \(y=0\) yields \(c_{13}=0\). Defining \(\delta_s^2 = \eta_p^2 - \beta_r^2\) and applying the boundary condition at \(y=H\) yields:

\begin{equation} \sin{ \left( H\delta_s \right) } = 0 \end{equation}

which implies that

\begin{equation} \beta_s = \frac{s\pi}{H} \end{equation}

with \(s=1,2,3,\ldots\) Therefore, the solution that we are looking for is:

\begin{equation} \phi_d\tau_d = \sum_{r=0}^{\infty}\sum_{s=1}^{\infty}c_{rs}\cos{ \left( \beta_r x \right) }\sin{ \left( \delta_s y\right) }\exp{\left[ -\alpha t \left( \beta_r^2 + \delta_s^2 \right) \right]} \end{equation}

Now, we apply the initial condition

\begin{equation} \sum_{r=0}^{\infty}\sum_{s=1}^{\infty}c_{rs}\cos{ \left( \beta_r x \right) }\sin{ \left( \delta_s y\right) } = \ldots \\ \ldots -\sum_{o=1}^{\infty} \frac{4q_x}{Hk\gamma_o^2 \sinh{\left(\gamma_o L\right)} } \cosh{\left(\gamma_o x\right)}\sin{\left(\gamma_o y\right)} \label{eq:d:crs} \end{equation}

Once more, to solve Eq. \ref{eq:d:crs}, we are looking for orthogonal function of the functions that multiplies \(c_{rs}\). We want to integrate these functions from \(x = 0\) to \(x = L\) to elimate the \(x\) dependence and from \(y = 0\) to \(y = H\) to elimate the \(y\) dependence. That is, we need a function that is orthogonal to \(\cos{\left(\beta_r x\right)}\sin{\left(\delta_s y\right)}\). The function that we are looking for is \(\cos{\left(\beta_u x\right)}\sin{\left(\delta_v y\right)}\). Multiplying both sides by this function yields

\begin{equation} \int_{x=0}^{x=L}\int_{y=0}^{y=H}\sum_{r=0}^{\infty}\sum_{s=1}^{\infty}c_{rs}\cos{ \left( \beta_r x \right) }\sin{ \left( \delta_s y\right) }\cos{\left(\beta_u x\right)}\sin{\left(\delta_v y\right)} dydx= \ldots \\ \ldots -\int_{x=0}^{x=L}\int_{y=0}^{y=H}\sum_{o=1}^{\infty} \frac{4q_x}{Hk\gamma_o^2 \sinh{\left(\gamma_o L\right)} } \cosh{\left(\gamma_o x\right)}\sin{\left(\gamma_o y\right)}\cos{\left(\beta_u x\right)}\sin{\left(\delta_v y\right)}dydx \label{eq:int1} \end{equation}

From Eq. \ref{eq:mnn} and \ref{eq:mn}, the left-hand side of Eq. \ref{eq:int1} will be non-zero when \(\delta_s = \delta_v\). Moreover, the right-hand side will be non-zero when \(\gamma_o = \delta_v\), so, we have \(\delta_s = \gamma_o\), which implies that Eq. \ref{eq:int1} will be non-zero for \(s = o\) and simplified to

\begin{equation} \int_{x=0}^{x=L}\sum_{r=0}^{\infty}c_{rs}\cos{ \left( \beta_r x \right) }\cos{\left(\beta_u x\right)} dx = \ldots \\ \ldots -\int_{x=0}^{x=L} \frac{4q_x}{Hk\gamma_o^2 \sinh{\left(\gamma_o L\right)} } \cosh{\left(\gamma_o x\right)}\cos{\left(\beta_u x\right)}dx \label{eq:int2} \end{equation}

Also note that for \(r=0\) we do not need orthogonal functions and we can integrate Eq. \ref{eq:int2} directly without using cossines. This is,

\begin{equation} c_{0s} = -\dfrac{\displaystyle \int_{x=0}^{x=L} \frac{4q_x}{Hk\gamma_o^2\sinh{\left(L\gamma_o\right)} } \cosh{\left(x\gamma_o\right)} dx }{ \displaystyle \int_{x=0}^{x=L}dx} \end{equation}

which yields

\begin{equation} c_{0s} = -\frac{4q_x}{HLk\gamma_o^3} \end{equation}

Back to the case \(r\neq 0\), we have

\begin{equation} \int_{x=0}^{x=L} \cos{\left(\beta_r x\right)}\cos{\left(\beta_u x\right)} dx = 0 \label{eq:ruu} \end{equation}

for \(r \neq u\), and

\begin{equation} \int_{x=0}^{x=L} \cos{\left(\beta_r x\right)}\cos{\left(\beta_u x\right)} dx = \frac{L}{2} \label{eq:ru} \end{equation}

for \(r = u\). Then we can drop the summation over \(r\) and solve Eq. \ref{eq:int2} for each \(c_{rs}\):

\begin{equation} c_{rs} = -\dfrac{\displaystyle \int_{x=0}^{x=L} \frac{4q_x}{Hk\gamma_o^2 \sinh{\left(\gamma_o L\right)} } \cosh{\left(\gamma_o x\right)}\cos{\left(\beta_r x\right)}dx }{ \displaystyle \int_{x=0}^{x=L}\cos^2{ \left( \beta_r x \right) } dx } \label{eq:int3} \end{equation}

The solution of the integral in the numerator is \begin{equation} \int_{x=0}^{x=L} \cosh{\left(\gamma_o x\right)}\cos{\left(\beta_r x\right)}dx = \frac{\gamma_o\sinh{\left(\gamma_o L\right)}\cos{\left(\beta_r L\right)} + \beta_r\cosh{\left(\gamma_o L\right)}\sin{\left(\beta_r L\right)}}{\gamma_o^2 + \beta_r^2} \end{equation}

which, from the definition of \(\beta_r\) (Eq. \ref{eq:d:beta}), becomes: \begin{equation} \int_{x=0}^{x=L} \cosh{\left(\gamma_o x\right)}\cos{\left(\beta_r x\right)}dx = \left( -1 \right)^r\frac{\gamma_o\sinh{\left(\gamma_o L\right)}}{\gamma_o^2 + \beta_r^2} \end{equation}

Therefore, the final solution of Eq. \ref{eq:d} is:

\begin{equation} \phi_d\tau_d = \sum_{o=1}^{\infty} -\frac{4q_x\sin{ \left( \gamma_o y\right) }}{HLk\gamma_o} \left\{ \frac{\exp{\left( -\alpha\gamma_o^2 t \right)}}{ \gamma_o^2 } \ldots\\ \ldots + \sum_{r=1}^{\infty} \left( -1 \right)^r\frac{2\cos{ \left( \beta_r x \right) }}{\beta_r^2 + \gamma_o^2 } \exp{\left[ -\alpha t \left( \beta_r^2 + \gamma_o^2\right) \right]}\right\} \end{equation}

Solution

The final solution is:

\begin{equation} T(x, y,t) = T_c + \phi_a(y) + \phi_b(y)\tau_b(t) + \phi_c(x, y) + \phi_d(x,y)\tau_d(t) \end{equation}

with \(\alpha = k/( \rho c_p ) \), and \(\phi_a(y)\), \(\phi_b(y)\tau_b(t)\), \(\phi_c(x,y)\), and \(\phi_d(x,y)\tau_d(t)\) expressed as:

\begin{equation} \phi_a = -\frac{S}{2k}y^2 + \left( \frac{T_s - T_c}{H} + \frac{SH}{2k} \right) y \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \lambda_m = \frac{m\pi}{H} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \phi_b\tau_b = \sum_{m=1}^{\infty}\left[ \dfrac{S}{Hk} \frac{ \left( -1 \right)^m\left( 2 - \lambda_m^2H^2 \right) -2 }{\lambda_m^3} \ldots \\ \ldots + \left( -1 \right)^m\frac{2}{\lambda_m}\left( \dfrac{T_s - T_c}{H} + \dfrac{SH}{2k} \right) \right]\sin{\left(\lambda_m y\right)} \exp{\left(-\alpha\lambda_m^2 t\right)} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \gamma_o = \frac{ \left( 2o - 1 \right) \pi}{H} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \phi_c = \sum_{o=1}^{\infty} \frac{4q_x}{Hk\gamma_o^2 \sinh{\left(\gamma_o L\right)} } \cosh{\left(\gamma_o x\right)}\sin{\left(\gamma_o y\right)} \label{eq:c:solution} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \beta_r = \frac{r\pi}{L} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \phi_d\tau_d = \sum_{o=1}^{\infty} -\frac{4q_x\sin{ \left( \gamma_o y\right) }}{HLk\gamma_o} \left\{ \frac{\exp{\left( -\alpha\gamma_o^2 t \right)}}{ \gamma_o^2 } \ldots\\ \ldots + \sum_{r=1}^{\infty} \left( -1 \right)^r\frac{2\cos{ \left( \beta_r x \right) }}{\beta_r^2 + \gamma_o^2 } \exp{\left[ -\alpha t \left( \beta_r^2 + \gamma_o^2\right) \right]}\right\} \label{eq:d:solution} \end{equation}

The flux/heat flux can be obtained by derivating these equations with respect to \(x\) and \(y\).

Using the Algorithm

The algorithm D2_HEAT_f.m was written as a function in Octave/Matlab and you can obtain it here. To use it, you will need to define the material properties and the maximum values for \(m\), \(o\), and \(r\).

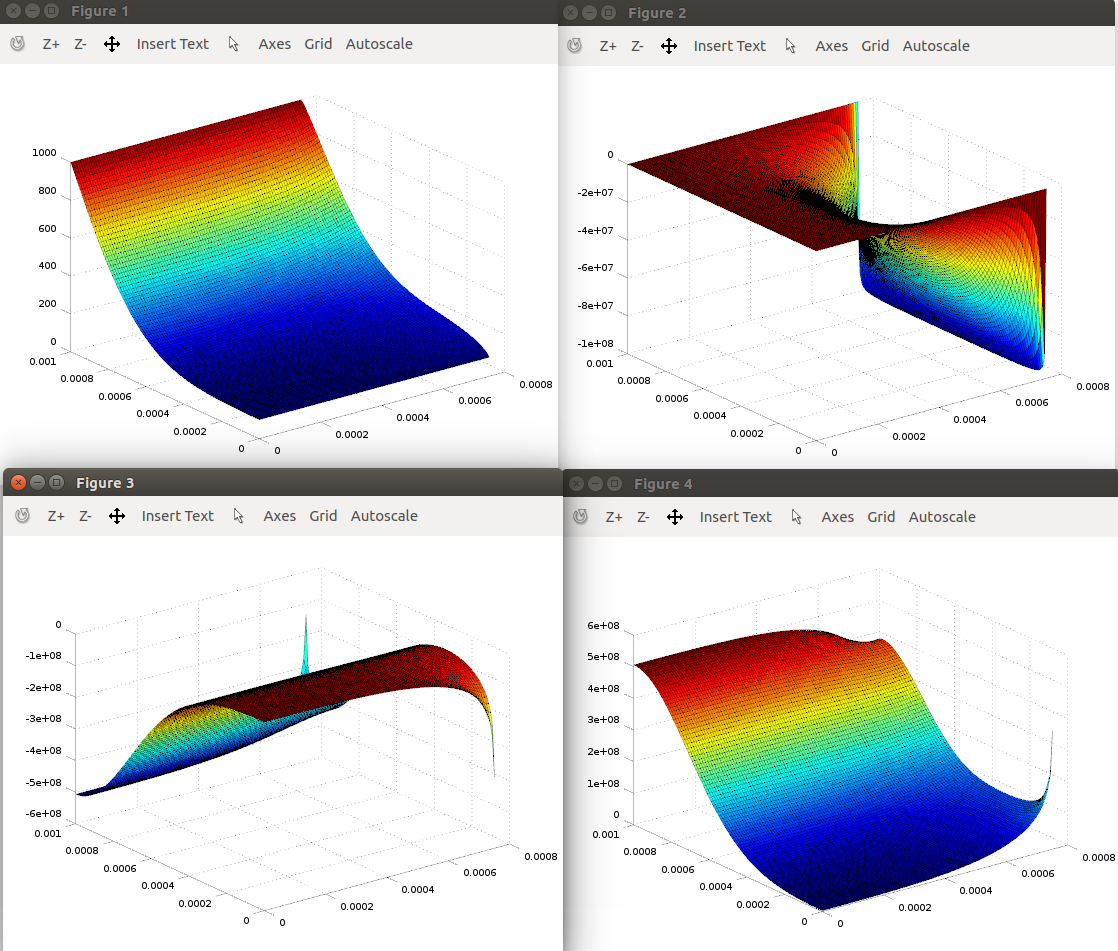

As an example, we can use the following script:

% Thermal properties

Tc = 100; % core and initial temperature (oC)

Ts = 1000; % superficial temperature (oC)

qx = 1e8; % heat flux at x = L (W/m2)

rho = 2700; % density (kg/m3)

cp = 900; % specific heat (J/(K-kg))

k = 205; % thermal conductivity (W/(K-m))

S = 5000; % internal heat source (W/m3)

% Material properties

H = 1e-3; % m

L = 0.75e-3; % m

yprime = 0:(H/100):H;

xprime = 0:(L/100):L;

y = repmat( yprime, 1, size(xprime,2)); % creating a subspace for y

x = repelems( xprime, [1:size(xprime,2); ...

size(yprime,2)*ones(1,size(xprime,2))]); % creating a subspace for x

% number of iterations

minf = 50; % for m

oinf = 100; % for o

rinf = 50; % for r

% time of the solution

t = 0.5e-3;

[Tprime, qxprime, qyprime] = D2_HEAT_f(x, y, L, H, t, Ts, Tc, qx, ...

k, rho, cp, S, minf, oinf, rinf);

T = reshape(Tprime, size(yprime,2), size(xprime,2));

qxout = reshape(qxprime, size(yprime,2), size(xprime,2));

qyout = reshape(qyprime, size(yprime,2), size(xprime,2));

surf(xprime, yprime, T)

figure;

surf(xprime, yprime, qxout)

figure;

surf(xprime, yprime, qyout)

figure;

surf(xprime, yprime, sqrt(qxout.^2 + qyout.^2) )which generates

Limitations

Every solution method has limitations. The most noticeable limitation is that we have to perform infinity sums to get predictions using solutions from separation of variables. Infinity sums, however, cannot be performed in numerical computations, which leads us to truncate the calculations for large values of \(m\), \(o\), and \(r\). How large these numbers have to be will depend on the problem geometry and on the material properties but, if theses number are not large enough, the calculations will manifest oscillations that will be most evident for predicted fluxes positioned near the flux boundary conditions (that is, near \(x = L\) in this solution). When observed that \(m\), \(o\), and/or \(r\) have to be increased, a rule-of-thumb is to double their values, re-calculate the predicionts, and observe if the oscillations have decreased to acceptable intensities.

Another surprising limitation is that the flux boundary condition at \(x = L\) is not satisfied when \(y = 0\) or \(y = H\). You can derivate Eqs. \ref{eq:c:solution} and \ref{eq:d:solution} with respect to \(x\) and observe that the term \(\sin{\left(\gamma_o y\right)}\) vanishes when \(y = 0\) or \(y = H\) no matter what is the value of the boundary condition. The solution, however, is accurate for \(y \rightarrow 0\) and \(y \rightarrow H\) and the concentration/temperature is not affected by this peculiarity.

Done

Now, you can go to: